INTRODUCTION

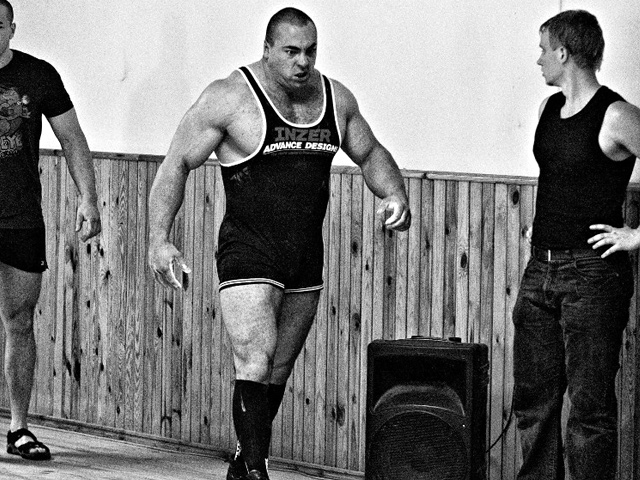

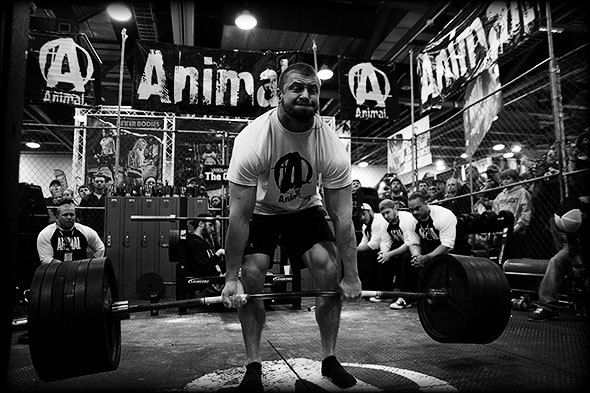

As we strive to be more active, healthy and mobile, the hips are put under a large amount of stress. With the increase in functional training, more emphasis is being placed on squatting, lunging, deadlifting and Olympic lifting. Functional exercises are essential in any training program, but for these exercises to be performed correctly, the hips must be able to transfer force from the ground and through the spine. When there is a minor deviation in hip movement, increased friction can occur inside of the joint leading to soreness. Many times after a training session we are experiencing appropriate muscle soreness, which is excellent and needed for increased strength gains. Post exercises soreness should be isolated to muscular tissue in the posterior or lateral hip. If you are experiencing anterior/lateral hip or groin pain the following article should benefit you greatly. Femoral Acetabular Impingement or FAI is becoming a more common pathology identified in the active population due to advancements in diagnostic imaging and clinical assessment. My goal for this article is to educate the reader on the anatomy of the hip, what is FAI, what causes FAI, symptoms of FAI, how to self assess if you are at risk for FAI, and lastly how to address any issues you may be experiencing through a series of corrective exercises.

HIP ANATOMY

Before we go any further, it is important to review the anatomy of the hip to ensure we are all speaking the same language as we move into the causes of FAI. The hip joint is a ball and socket joint consisting of the head of the femur (ball) and the acetabulum (socket). Below are two images of hip boney anatomy. In the figure to the left, we can clearly view the head of the femur and the acetabulum, which are surrounded by various ligaments and joint capsule to encompass the “hip joint”.

The hip joint is a very complicated joint from a ligament and muscle standpoint secondary to multiple connections from the trunk, shoulder, hip and thigh musculature. For the sake of the topic of this article, we will not dive into all of the ligaments and muscles of the joint, but I would like to point of some key structures which play an important role in this pathology.

Iliopsoas AKA “hip flexor”: this muscle attaches from the lumbar spine to the femur (thigh bone) and acts to flex the hip. When this muscle is overly tight, it can cause excessive anterior tilt in the pelvis and lead to abnormal alignment of the hip joint. Picture of muscle seen in with arrow in image to the left.

Gluteals: there are 3 gluteal muscles that attach from the back of the ilium (hip bone) to the femur, which combine to extend/abduct the hip. When these muscles are weak, it can lead to poor knee control during squatting and lunging. Poor knee control can lead to poor mechanics, which encourage hip impingement.

Deep hip external rotators: this muscle group consists of many small muscles that attach from the sacrum (tailbone) to the femur, and act to externally rotate the femur. When these muscles are weak, the knees have a tendency to cave-in (valgus) during a squatting motion.

CAUSES

The causes of FAI are currently not completely understood, though it is hypothesized that faulty mechanics during daily activities and squatting can cause excessive compression between the neck/head of the femur and the rim of the acetabulum leading to impingement. When excessive contact between these two structures occur, bone growth can form, which leads to a CAM or Pincer type deformity shown below. A CAM lesion is an abnormal formation of bone growth on the neck/head of the femur, which leads to increased contact between the femur and acetabulum causing a pinch when the hip goes into flexion/adduction/internal rotation. A Pincer lesion is an abnormal formation of bone growth on the outer rim of the acetabulum, which also leads to increased contact between these two structures. While CAM lesions are more common in males, and Pincer lesions more common in females some studies suggest 86% of symptomatic people experience a combination of both deformities.

In an attempt to understand what faulty mechanics might possibly cause CAM and Pincer deformities, many studies have identified excessive hip flexion/adduction/internal rotation as the culprit. The image on the left demonstrates a view of how a lesion may appear while the image on the right dictates the classification for each lesion.

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of FAI can vary and for the sake of this article, we will address anterior hip FAI opposed to posterior hip FAI when discussing possible symptoms. Many individuals who have been diagnosed with FAI have the below complaints:

- Pain in the upper groin area or from front to lateral hip

- Deep ache that commonly cannot be palpated

- Insidious onset

- Pain with activity (deep squatting or lunging)

- Difficulty sitting

- When severe, pain with putting on shoes/socks

It is important to note that though you may be experiencing one or two of these symptoms, you still may not have pathology. Many time symptoms of FAI can be confused and misdiagnosed as a hip flexor or groin strains. If one side feels different than the other, caution must be taken when training into positions of deep squatting, lunging, twisting and higher impact plyometrics without consulting a physical therapist or orthopedic specialist.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

In this section we will go over some self assessment techniques to help you determine if your are experiencing symptoms that may be associated with FAI, though these movements are in no way a substitute for a professional clinical examination from an orthopedic specialist, physical therapist, or surgeon. There is a limit to ones ability to perform self-assessment, and an orthopedic specialist will use a variety of special tests and diagnostic testing to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

Squat test: stand with your feet hip width apart (narrow stance), toes pointing forward and arms overhead. Keep your elbows locked overhead, toes pointing straight forward and your back as neutral as possible, squat down as deep as you comfortably can go. This test is positive if you feel a pinch in the anterior/medial groin. *This is more of a clinical assessment, not a test that has been validated in the research.

Hip flexion test: Lye on your back with both legs straight. Pull one knee to your chest without letting your knee rotate to the outside. Note how high you can flex one hip compared to the other. Test is positive if you feel a pinch in the anterior/medial groin or there is a significant difference in range of motion between the two sides.

*This is a self-assessment of your hip flexion range of motion. Many times hip flexion range of motion is poor with individuals who are experiencing hip FAI. This is more of a clinical assessment, not a test that has been validated in the research.

FABERS test: Lye on your back with both legs straight. Bring one foot to the opposite knee and let your knee drop to the ground. Note the difference from side to side. Test is positive if there is a significant difference in flexibility from side to side or there is a pinch pain in the medial groin region.

Thomas Test: Lye off the edge of a table, rock back holding both knees into your chest. Keep your back flat against the table at all times, grab one knee while you let the other knee fall to the ground. Repeat for the opposite leg. Test is positive for iliopsoas (hip flexor) tightness if your thigh does not go flat onto the table, positive for quad tightness if your knee cannot bend >80deg at the bottom of the movement.

*If these tests are positive, it does not mean that you have pathology. These tests will simply identify movements, which cause impingement in the hip. To get an accurate diagnosis of your pain, an orthopedic specialist or surgeon should be consulted.

ACTIVITY MODIFICATION

While no one likes to change what they are doing in their normally daily routine, research has been shown to significantly decrease FAI hip pain with simply changing daily habits that may be contributing to continued irritation. Below is a list of activity modifications that should be performed if you are experiencing above stated signs and symptoms:

- Sitting: sit with hips in external rotation as opposed to knees together

- Eliminate sitting with legs crossed

- Side sleepers: sleep with pillow between your ankles and knees. Avoid excessive hip flexion while sleeping.

- Sumo squat opposed to squatting with a narrow stance

- Avoid biking as this causes excessive hip flexion

These activities should be modified until symptoms are completely reduced. Once symptoms are eliminated, caution should be taken when returning to normal activities.

STRETCHING

Stretching and regaining normal range of motion and flexibility is extremely important when addressing deficits related to FAI. I would caution from “over stretching” the hip as this can cause irritation within the joint. Extreme caution must be considered when performing below stretches. Stretching for hip FAI includes the use of an elastic band, as the elastic band will help create slight traction in the joint; therefore, decreasing the risk of impingement and increasing the stretch of the tissue being addressed. Stretching performed prior to a training session should be dynamic and be held no longer than 5 seconds, while stretching post training should be held for duration of 20-60 seconds based on age (longer holds for increased age). All stretches should be performed for 2-3 sets for optimal flexibility gains.

- Kneeling hip flexor

- Prone quad

- Quadruped adductor

- Quadruped glute

- Supine hip flexion

While not all of these stretches will need to be performed daily, areas of tightness are going to need to be addressed to make significant gains. If the Thomas test above was positive, more attention is needed to the quads and hip flexor.

If the hip flexion assessment listed above was significantly different than the non-involved side, pay more attention to the hip flexion stretch. The glute and adductor stretch are great for preparing the hip for the sumo squat position listed below. If any soreness or pain is felt with stretching, be sure to immediately stop that given stretch. Do not try to push through any discomfort with these stretches, and contact your local physical therapist or orthopedic specialist if you are experiencing negative results with the above listed stretches.

CORRECTIVE EXERCISES

Corrective exercises are just that, corrective. These exercises are not huge strengthening exercises, especially in the beginning phases as proper muscle activation needs to be achieved before advancing to more functional positions. These exercises are broken up into 3 phases and are intended to ensure proper muscle activation in phase 1, increased difficulty in phase 2, and muscle hardening in phase 3. All of the exercises listed below or intended to decrease the tendency for the hip to obtain the position of flexion/adduction/internal rotation, which we now understand from research are the compromising positions of hip FAI. Each phase has a purpose and should not be skipped or overlooked. An individual can move on to the next phase when the appropriate sets and reps are met with minimal fatigue, perfect form, appropriate muscle activation, and no pain with any exercise. *For exercises not pictured below, a quick google search will do the trick. Pictured below are the less commonly understood exercises.

PHASE 1 (3x20reps)

- Sidelying clam

- Sidelying hip abduction

- Donkey kick

- Bridge

PHASE 2 (3x15reps)

- Standing band clams

- Band walks

- Single leg RDL

- Sumo squat w/band around knees

- Bridge on ball

- Glute/ham raises

PHASE 3 (3×8-10reps)

- Single leg squat (increasing depth)

- Split squat w/band

- Single leg RDL w/band (same band position as split squat)

- Sumo squat w/weight

- Single leg bridge on ball

- Glute/ham raises (add weight)

Incorporating these exercises into your daily routine is going to be a huge part of being successful in addressing hip FAI. If performed correctly, these phases can be progressed through in 1-2 week blocks. Once you have completed the final phase, incorporate as many phase 3 lifts as you can into your normal training routine. Review your training with your strength coach to come up with the best possible program. I would also encourage performing phase 1 exercises (1 set) prior to heavy squatting days to ensure your hips are properly activated prior to loading. Stretching can be continued throughout life as staying mobile in your hips will allow for full movement and continued strength gains throughout your training.

I hope the above information has helped open your eyes to an increasing common pathology that has been surfacing in the Olympic lifting and Cross Fit community. As previously discussed, if you are experiencing pain with the above listed stretches or exercises, please stop them immediately. If you continue to experience hip pain you should schedule an appointment with your local physical therapist or orthopedic specialist to undergo a thorough evaluation of your condition. Hip pain can arise from many different pathologies, and hip FAI should be considered if there is continued anterior hip pinching felt with daily activities or after training Please feel free to contact me with any further questions or concerns you may have.

If you have found the above information helpful, you can also view my Ebook “Body Mechanic” through the Juggernaut online store. Link with description of content is listed below.

Nejnovější komentáře